GR: Thanks for agreeing to let us interview you for Gyroscope Review. We’re pleased that you are one of our contributing poets. Will you please begin by telling us where you’re from, where you write, and why poetry?

TT: I was born in Brooklyn, New York, in the section that’s recently gone hipster: Bushwick. When I was one, my family moved to suburban/development Long Island. I escaped from that asylum when I was sixteen.

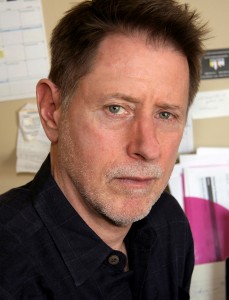

I returned to Brooklyn two years ago. I live (and write) in the hipster-free zone of Bay Ridge, in a little cubbyhole office in the apartment I share with my wife. The office has two large windows that look out over green backyards, white garages, and, in the distance, red brick apartment buildings that in late afternoon sunlight look like Edward Hopper paintings.

Why poetry? The music and devices of poetry sink their hooks in you very early, don’t they? Blake, Poe, “Tyger tyger, burning bright,” “napping/tapping/ rapping/rapping…” I had those rhythms in my head when I was eight, nine, ten. Then, the music of my adolescence—Beatles, Dylan, Joni Mitchell—highlighted dexterity with language. Irony, paradox, interiority. “I think a no, I mean a yes,” “noon/spoon/ balloon/moon/soon,” “greens/jeans/roses/scenes/discloses…” You start to repeat, you start to imitate. You can’t help it, it just happens in your head. Then it starts to become your own. Sometimes I wonder why everyone isn’t writing poetry—maybe they are. They must be hearing it, thinking it.

GR: Who, or what, are your poetical influences?

TT: I found Jason Shinder’s posthumously published book, Stupid Hope, influential. The frankness, the simplicity, both of which generate depth. And the shapes of the poems—often single lines mingled with couplets in irregular patterns. Charles Wright, too. The space on the page, the drop lines. His poems feel as if they’re happening the way clouds drift across the sky.

GR: How do you decide what ‘form’ a poem should take?

TT: Sometimes the form appears straight out, draft one. But I always test it – I try it this way, that way, any way, print it out, look at the hard copy, before I decide. If I’m lost, if I’m not really seeing it on the page, I count syllables. “Mescaline” and “Broken Things” happened (forgive me if that sounds pretentious) on the same morning, out of the same mood, and their final form is very close to their first drafts. I knew it as soon as I saw them. Others—the “Chris Lunn” poem, for instance, in Gyroscope—literally required many years, numerous attempts, and multiple drafts before it resolved.

GR: What is your writing process like?

TT: When we’re home, generally very disciplined, but not in a martinet kind of way. I have a sense of what I want to work on on a given day. I look at e-mail, scan a few headlines, make breakfast. These days, I have the laptop with me while I eat and have coffee, but I don’t get to the poems or fiction until I’m back in the office. When we travel, I try to recreate the home practice, but with necessarily irregular success. And when classes are in session (I teach in NYU’s Global Liberal Studies program), I struggle, especially around times when student work comes due.

GR: Do you belong to any writer’s groups – face-to-face or online? If so, are they part of your process?

TT: Here’s a variation on one of my favorite Raymond Carver answers: no, and yes. No, in that I rarely show any one any work in process, ever. Most often, I arrive at a point where I’m OK with the work, and I send it out. Feedback comes in the form of rejections, and the occasional acceptance. But … if I’m working on something new and different, if I need a shake-up, or just a shot of validation, I’m happy to participate in some kind of group work, get some feedback, fresh eyes and ideas, and maybe generate some new stuff. So in that sense, yes, in that over last six or seven years, I’ve taken Master Classes at Poet’s House with Dorianne Laux, Carol Muske-Dukes, and Alison Hawthorne Deming. And I did private sessions with Kim Addonizio. These are all great poets, they put together rosters of great participants, and I got so much from each of the sessions.

GR: What do you look for in the poetry you like to read? Any favorite poets?

TT: I love the work of the poets I just mentioned. The writers I value the most are the ones who make me want to write, and in that sense, I find Kim Addonizio invaluable, particularly her short stories. I read an Addonizio story, I write two of my own, that kind of thing. The great Filipino poet Merlie Alunan said, “Poetry isn’t about the words. Poetry is about the silence after the explosion that the words cause.” I look for poetry that explodes, then leaves me in that silence. Joseph Legaspi, Marjorie Evasco, J. Neil Garcia, Krip Yuson (Filipino poets, all), they do that for me. Larry Levis, Franz Wright, Joy Harjo, Mary Oliver … Leonard Cohen, the Kenneth Rexroth translations of Chinese and Japanese poets. I could go on.

GR: What is the most important role for poets today?

TT: To bear witness. And these days, in order to do that meaningfully, I think it’s necessary to travel, to complicate your perspective by living in someone else’s. And then to tell the truth, but tell it slant. It occurs to me that Emily Dickinson did not hop around the globe, and she was able to bear witness… In workshops I tell my students that everything I say is right, but it’s also wrong. This might be one of those cases.

GR: Which poets have you had the opportunity to hear read? Alternatively, what is the most recent book you’ve read?

TT: Ricky de Ungria is a great reader, animated and implicated. Chris Abani. Kwame Dawes. Michael Dickman shows you the power of silence. Jacqueline Bishop is an excellent reader. Donna Masini.

Novels: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, and Omar Musa’s Here Come the Dogs—these really grabbed me. Poems: Breakable Things by Loren Kleinman got me tapping the keyboard.

GR: Any future plans for your work that you’d like to talk about?

TT: In October 2015, my chapbook Yolanda: An Oral History in Verse (Finishing Line Press) appears. It’s unlike anything I’ve done before, kind of a hybrid of immersion journalism, oral history, and found poem. It chronicles, in their own words, the experiences of survivors of Super-tyhpoon Yolanda, which devastated the islands of Leyte and Samar, Philippines. In Fall 2016 Winter Goose Publishing will bring out my first poetry collection, Requiem for the Tree Fort I Set on Fire. Currently, I’m nearing the finish line of a novel-in-stories.

GR: What other interests do you have beyond literature?

TT: I’m an avid scuba diver. I do most of my diving these days in the Philippines, where my wife is from. I maintain a regular yoga practice, which keeps my head on straight, if upside down. I’m a slave to music: Tammy Wynette, Duke Ellington, Pet Sounds, Brahms’ Symphony No. 3. And I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the not-for-profit organization I helped co-found and currently direct: New York Writers Workshop. We’re a collective of New York-based writers who teach here, there, and anywhere. We’ve been in Australia, Europe, all over Asia, and quite a few places here in the US. Our slogan: coming soon to a continent near you.

GR: Thank you for sharing your thoughts with us. Please let our readers know where they can find more information about you or your work.

TT: Here’s a link to an interview concerning Yolanda, on Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/loren-kleinman/tim-tomlinson-talks-about_b_7771346.html

Some recent poems in Lunch Ticket’s Amuse-Bouche, all of which draw from the Philippines. http://lunchticket.org/the-koreans-terminal-3-farewell-in-the-eel-grass/

A piece of fiction from my novel-in-progress: “Gun.” http://thecoachellareview.com/fiction/gun_timtomlinson.html

New York Writers Workshop: http://www.newyorkwritersworkshop.com/

You can also find Tim Tomlinson’s poems, “The Goldfish,” and, “For Chris Lunn, Who Became a Paraplegic at the Age of Twenty, in an Automobile Accident Near Setauket, October 1974,” on pages 10-11 of Issue 15-2 of Gyroscope Review.